"Connected to art is part of the treatment".

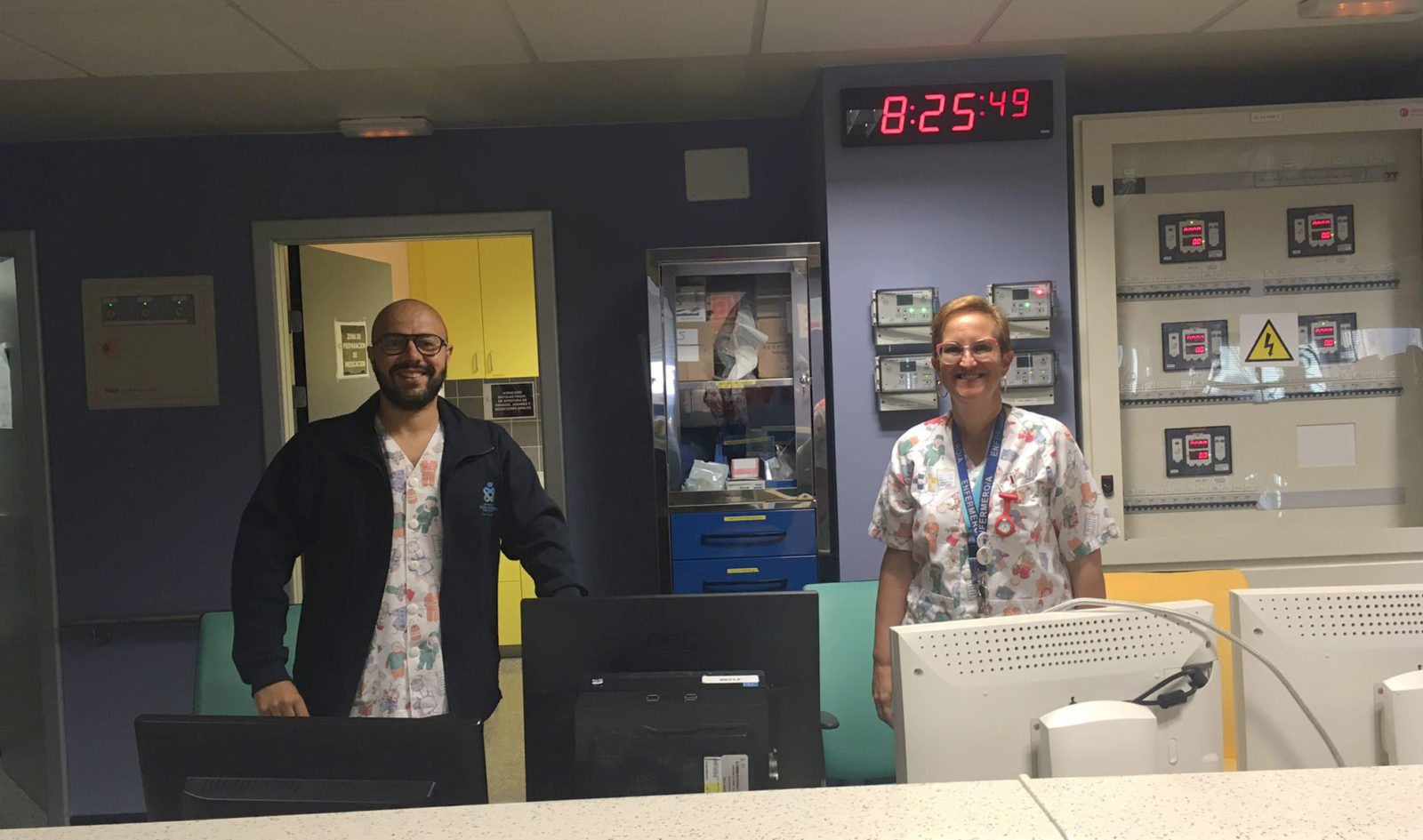

We share with you the interview with two of the five UCI Paediatric ICU comitents, Lili Quintero and Quique Chinea.

After the punctual applause at 20:00 hrs (19:00 hrs in the Canary Islands) to all the health personnel in full confinement, calm arrives. In hospitals and paediatric ICUs, in particular in the Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria where our Tenerife concomitance takes place, this calm never arrives. The hectic daily routine accompanies health workers in carrying out a job that is as invisible as it is key to our society. Accompanied by a devotion and dedication to the patient, to give the best of themselves every day, the members of the paediatric ICU nursing team at this hospital in Tenerife share with us how they came to put on their uniforms and make this profession a way of life that changes the course of many people's lives.

How are you and how have you experienced the pandemic?

LILI QUINTERO: Within our healthcare work, it has undoubtedly been the most complicated year we have experienced. Very difficult because, despite working in the ICU and the challenges we face every day with our patients, we had never faced a pandemic before. The first death in China at the beginning of 2020, we always saw it as something distant and we didn't have much information about what was happening and how the virus was transmitted, although the public health services were already starting to give us warning signals. When we saw it on European soil, we literally started to tremble when we saw the level of work and stress in the hospitals. We continued with the optimism of “it's still a long way off”, until the end of February when we saw the cases in Madrid and, from one day to the next, we arrived at the hospital and were told that we had to take the PCR test of our hospitalised children and turn everything upside down. Once our patients were all negative, we moved them to the neonatal unit boxes and started working with adult patients. The problem with COVID patients is that they are difficult to stabilise, and we also didn't know what kind of treatment would work best for them, so we gradually tried different therapies.

QUIQUE CHINEA: From one day to the next, we started taking children to adults, with all that that entails. Since June, we have resumed our care activity with children, with all the restrictions that are still present in the hospital today. It has changed the way we work, just the mere fact that the children can't see our faces, that we can't give them a smile, is something we miss very much.

«Normally people criticise healthcare, but if you talk to people who have had a serious health problem and have been admitted to hospital, things change, because you start to become aware of the work that is done. In our day-to-day work we do everything we can and much more, patients leave very grateful and so do their relatives».»

In health care, the work of nurses and carers is invisibilised in the media. Has the pandemic changed this?

L: At first, with that daily applause, the hair on the back of my neck stood on end. Unfortunately, perhaps because of the level of information we have in our society, we see how our work has once again been pushed into the background, it is only when you really need it that you remember such important issues as health and education, it is a problem to live in a society with such a capacity for forgetfulness. We have always seen ourselves as the middle of a sandwich, those in the middle are the forgotten ones, and those in the top layer are the most visible doctors with the greatest social recognition. It is a beautiful profession, but a thankless one.

That leaves the vocation, how did you become a nurse?

Q: I wanted to study physiotherapy, because I was involved in sport and I was interested in the recovery of sportsmen and women, but in the end I didn't get the grades and I went into nursing. I liked it more and more every day, and now in June I will be 21 years as a nurse. In my first days on a ward, with 30 patients in my care, I did ask myself: where have I got to? Is this what I want for the rest of my life? Will I be able to stand it? Yes, I have already realised that I can. It is a career that demands a lot of responsibility, commitment, concentration and maturity.

«In my case it was not vocational, but a love story. I had a classmate in COU who was in love with the profession and we had a competition to see who could get the best marks, and in the end I managed to get in and he didn't. I started the degree without being sure, but from the first year with the internships it was already in my blood. I started the degree without being sure, but from the first year with the internships I got into the vein, I was won over by the patients, in this case not the paediatric ones but the elderly. There were existential crises along the way, when I had to learn to manage very complex situations on my own, for which you are given no preparation».»

Did you already like children before you became a parent?

Q: It's not that before becoming a father, I have an eight-year-old son, I didn't have empathy, but it changes your perspective and makes you value what you have at home, your health and give importance to what really matters. Life is very fragile and everything can change at any second.

L: I had a clear existential crisis, not when I became a mother but when I became an aunt. I had to reconcile with myself and learn to differentiate between my personal life and what happens in the hospital, otherwise it is not possible to have a healthy and happy life.

Direct contact with the patient leaves many anecdotes, any that come to mind?

L: I especially remember a little girl, with Down's Syndrome and a heart condition, who was there from the age of 2 to 8 months, and whom we treated as if she were our niece. I also remember another child, now 16 years old, who fell from a height of more than 15 metres with a serious polytrauma. I will always remember the very special night we spent during the Eurovision gala, when he had just woken up.

Q: I think of a teenager, admitted at the age of 14 for a tumour, not very aggressive, but which was in a compromised area, so that he was left quadriplegic after the operation. Today, at almost 20 years old, he comes to see us and walks very well, he even got his driving licence. I also remember a girl who fell from a great height, with a broken spine and a shattered ankle, a year later I saw her jumping on the beach. In 2010, an Irish girl was on holiday with her family and was operated on for appendicitis, but in the end she had a much more serious condition which meant she received many blood transfusions, so when Spain won the World Cup she could boast that she had Spanish blood. Last year she went to Liverpool University to study social therapy and still comes to Tenerife on holiday and visits us.

How did you become part of Concomitentes?

Q: The link is through our mediator, Felipe G. Gil, whom I have been good friends with for many years. On a trip, over a beer, I tell him that I want to take on new challenges in the workplace and I tell him about the need to help the children to get to know their stay in the paediatric ICU better.

«After a while he told me about Concomitentes and how my idea could fit in, so I convinced the people in the team most like me to join. This was not too difficult, as three of them are my best friends and the other one is my partner. So it all started from a conversation between two friends and a series of coincidences that has led to us being here today».»

What has this two-year journey been like?

L: For me it's been taking me out of my comfort zone and experiencing a world I was totally unfamiliar with, it's been fantastic and an opportunity to have a new vision of what we can do in the unit. I am looking forward to the end result, but also sad to see it end. I would love to keep in touch with the interesting people I have met and get together again.

One lesson you would take away from this adventure?

Q: When you relate to people in your own circle, you don't realise the importance of your own work, you don't value it. With this project we reaffirmed that we have a very important job, that we do relevant work. I also remember the exchange we had in Madrid with the commissioners of other projects. We feel we are in the place where we have to be, valued as professionals.

L: When you get used to being a professional, it is part of your daily life, and you don't see it as something exceptional. But I have had the feeling that our work and value within healthcare, as the great carers of people, is not known. I have been surprised by the curiosity we have generated, so I would highlight the humanisation of hospitals, helping patients more and making hospital work more visible.

How do you perceive the role of art in the health field?

Q: The hospital has a budget, and anything that is not medical is left out, including art. There are many initiatives, often coming from the private sector, that are connected to art, and that is part of the treatment. Keeping the patient entertained and happy is going to help their recovery.

«It's a job in which the benefit of one has an impact on the other pieces».»

Your audience is you, the patients and their families. How do you work from this multi-perspective?

L: When we started we had a clear idea of benefiting the children and their families. However, with the ideas that we were getting from each other, we saw that this was also going to help us to better reach our patients. The project will provide us with tools to better reach each patient profile, to help patients cope better with their situation in the ICU and to help parents who have to delegate and entrust the care of their children to others.

What do you expect to be left of this work once it is completed?

Q: As one of our clients, Ruyman, says, we want this to be our legacy. Our aspiration is not always to work in a paediatric ICU, so we want to leave this work as the beginning of something more so that, both in our hospital and in others, we begin to treat not only the illness, but also the emotional aspect, something that we have verified with the research of the psychologist, Sara Miguel. This project will be the beginning of something more.

Concomitentes

Concomitentes