Ancestors and ghosts

An account of the progress of the Extremadura project and the process of imagining the artistic commission.

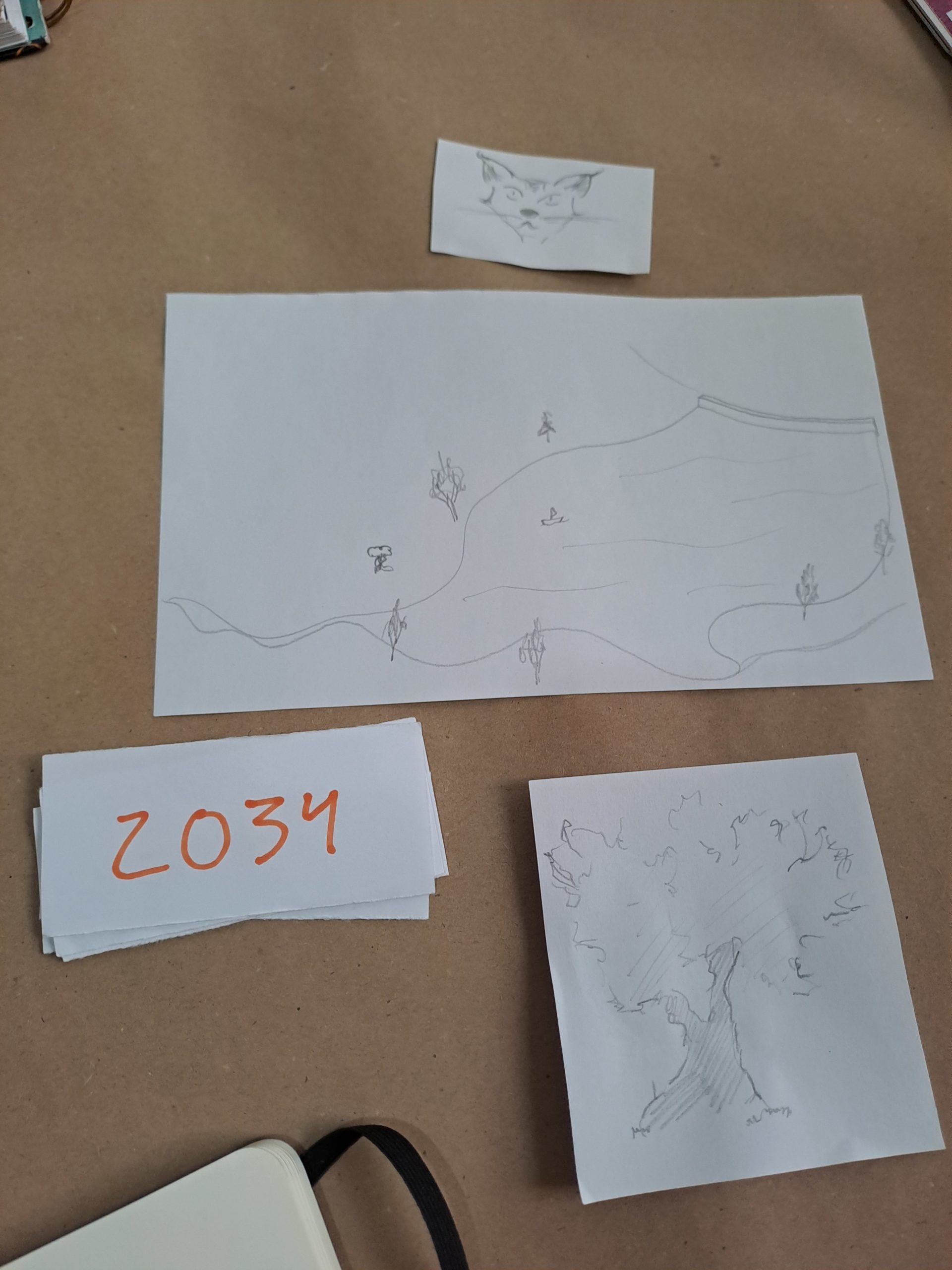

In the first sessions of 'Non plus ultra' we talked about drought, the springs, the rainfed olive trees that are being converted to irrigation, the problems of local water (with very high levels of lime), the devastating image of empty reservoirs... Water appears as an image of pain. It is difficult to look beyond the economic and political conflicts that have hijacked it. Trying to navigate this tangle, one Sunday morning sitting on some rocks behind the Ermita de la Estrella in Los Santos de Maimona, we read Sophie Lewis: I define "amniotechnics" as the art of enduring and caring even when they tear you apart, while sustaining you [...] I continue to argue that we should pay attention to the technologies we use - borders, laws, gates, pipes, bowls, boats, bathtubs, pipes and scalpels - to control, release and direct water. When is it time to release a border? When is it time to keep a space (like a cervix) firmly sealed? At what point (like a cervix) can the wall be torn down? When can a bandage be removed? How can a city be open to outsiders and closed to tsunamis? ("Another surrogacy is possible: Feminism against the family", 2020).

Water in 'Non plus ultra' is a material problem, but it is also a metaphor for the difficulty of rooting and projecting exciting futures in the non-urban south of Badajoz. Going round and round the problem of water leads us to think about the technologies that control it, here, where Franco's hydraulic policies that dotted the landscape with canals and reservoirs are so important; technologies that manage the materiality of water, but also its symbolic power: how can a generation of young people imagine themselves in the future if the shadow of the desert lurks, the image of a wasteland where it will be hotter, cool places will evaporate and access to drinking water will be increasingly difficult?

We talk about these issues and there is a constant nostalgia for a time when fountains were meeting places, public spaces where people could share, talk, generate community. These images are in the imaginary of the group of people who have commented on them, but almost nobody has lived them. They illustrate a lost past, devastated not by drought, but by a progress that scorns any reference to a different world. Washing clothes with a machine and not having to do it by hand may be an obvious improvement, but in that transformation it was forgotten that the fountains were more than just reproductive work spaces, and we find places like the Plaza de Llera, where they built a cement and tile stage over the old fountain, hiding it. The walls of the construction are chipping away due to the humidity of the spring, which continues to flow underground; not everything can be covered with cement. There are other villages, such as Valverde de Burguillos, where after years of oblivion, they are trying to recover the collective memory surrounding the water. They have managed to have the "water culture" declared an Asset of Cultural Interest and are trying to reactivate the fountains, pools and troughs so that they can once again become spaces to inhabit, a task that is not easy.

In the sessions of 'Non plus ultra una' we talked again and again about the difficulty of recovering meeting spaces around water, there are fewer and fewer places of sociability in towns that do not involve consumption and bars are becoming more and more similar to each other, with a white led light that homogenises like an Instagram filter. We fail to understand how this imaginary has been imposed, how the image of something we identify with "urban" is multiplied. This neoliberal violence - which privatises meeting spaces, imposing the consumption of a capitalist culture as the only form of communication - wipes out what remains of times gone by. The most terrible thing about this process is that the destruction of a way of inhabiting villages is a double-edged danger; it can lead to a nostalgia for a time that the younger (and no longer so young) generations have never known. The uprooting produced by the destruction of rural culture tempts one to long for a return to a time, to habits and to an inaccessible landscape, which has already disappeared. In her book "Arde la sed", María Sánchez concentrates this sadness in the following verses:

The ancient seas

now sleep on the stones

bravíos flourished

it is no longer raining no

it doesn't rain like it used to

over and over again they repeat

the elderly

they were born

before the end

they will become ancestors

we in ghosts

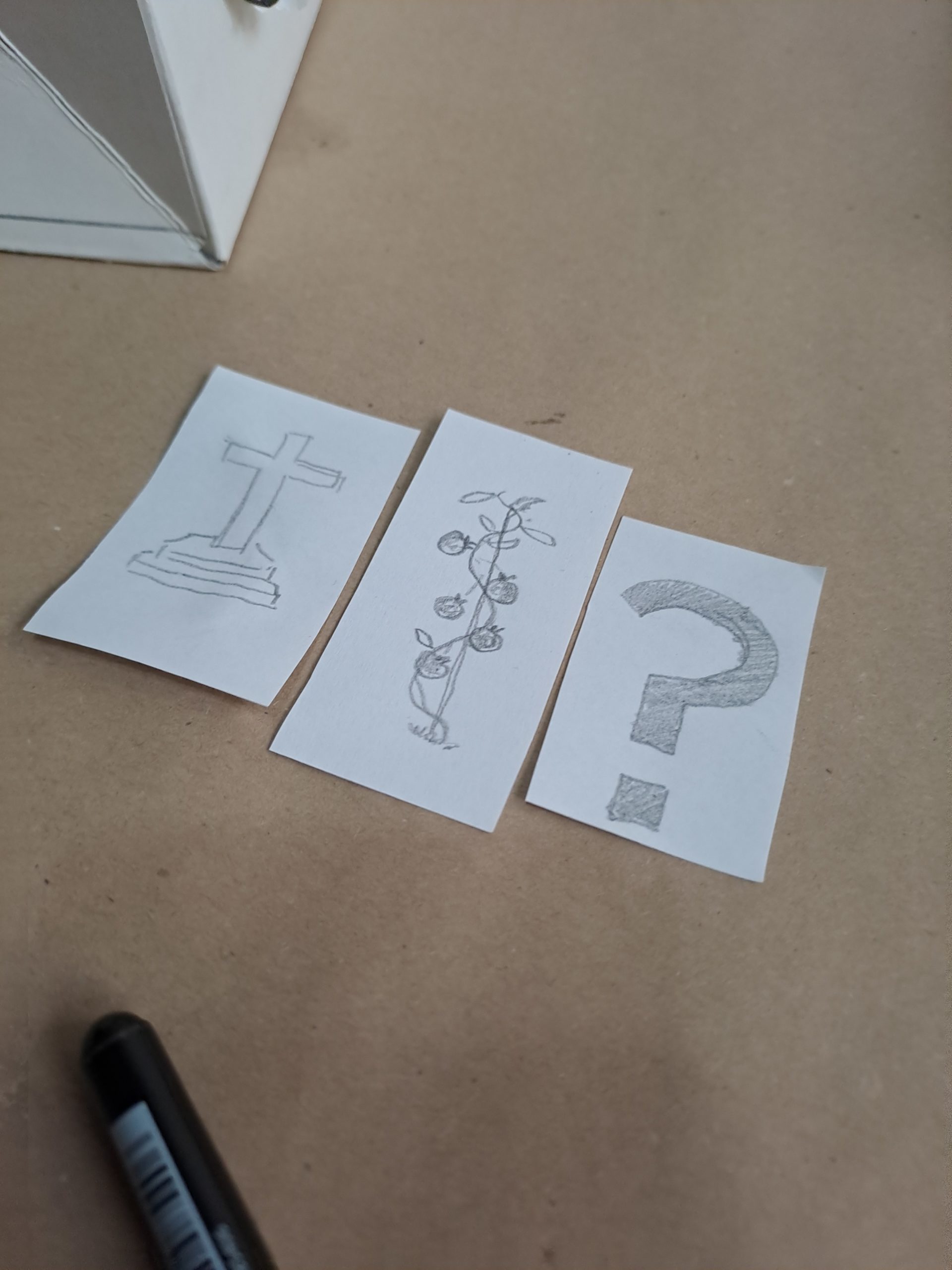

We inhabit the loss of a world and in becoming aware of this I am terrified that this process will not only be harmful in the present but will also become a wound to be inherited by future generations. The challenge for the commissioners of 'Non plus ultra' is to propose a commission that transforms the image of the south of Badajoz as a land doomed to drought and extractivism. So far we have focused on analysing the problems that beset water in the region (the mega solar parks that dry up the soil, the accelerated depletion of aquifers due to the increase in irrigated crops, the leviathan of open-cast mining for the digital transition that will happen far from here...) and on understanding the present threats and the chronology that has defined Extremadura as a land boxed in between the dynamics of internal colonialism and the old-fashioned nostalgia of an archaic "race of conquerors". But the more we analyse the context we inhabit and these diffuse urbanities (for the urban is not a territory, but forms of life that extend from centres) that infiltrate everywhere, the more we recognise a danger that has made its way into our complaints: being unable to move beyond a narrative of pain and anguish, of melancholy for a time gone by (that was never better), and only being able to despise the time we actually inhabit.

To avoid becoming ghosts of a time we never lived through, we need to reconcile ourselves with these landscapes, which at the beginning of June are a thorny dry yellow. The commission of 'Non plus ultra' must find a way to "re-enchant" the territory and avoid turning it into a generational trauma. It is a complex but not impossible task, and there are many ways of doing it: digging into the common memory and finding stories on which to build, generating collective dreams that escape the imaginative drought of the present, thinking of ways to link ourselves with other generations (past and future) through care, learning about critical situations from other times and spaces that help us to share tools and solidarity strategies...

Lewis spoke of "enduring and caring even when they tear you apart, while sustaining you", I think it could refer to the relationship with this Extremadura landscape in times of ecosocial crisis. The commission begins to define itself and points to the need to intervene in the imaginaries and infrastructures that prevent us from re-enchanting the land. "Re-enchant" is a beautiful term, I take it from the book "Re-enchanting the world: feminism and the politics of the commons" by Silvia Federici and it speaks of a collective desire full of imagination. I would like to talk to María Sánchez to better understand what she thinks when she writes "ancestors"; for me, the difference with ghosts is that ancestors have a connection with the earth that allows them to pass on knowledge. We need to link ourselves to the soil from the soil in crisis that we inhabit in order not to be ghosts and to re-enchant these comarcas. We have to do it as a reparative task, not only of the landscape, but also of the climatic traumas. We have to do it with joy.

Concomitentes

Concomitentes