Making sense of the world, water and drought

This was the second edition of 'El agua brota sin avisar'.

A year ago we danced and sweated to call the rain. We celebrated the encounter and invoked the impossible with the first edition of "Water gushes forth without warning"inhabiting a quarry, a saw milled by extractivist grammars, to remind us that there are no empty places, but silenced ones. The first event "El agua brota sin avisar" brought together the group of Non plus ultra comitentes and invited more people to a collective action to use artistic practice as a way of visualising the networks and histories that exist in the south of Badajoz, to show an imaginary that resists the logics of drought and depopulation. We invoked a rain that was as literal as it was symbolic: a rain of stories, of encounters, of diverse voices and possible futures.

And it rained. It rained a lot. The reservoirs and aquifers drank, the countryside was grateful in many places and in others suffered the cruel consequences of uncontrolled urban planning and negligent policies. In Badajoz, during the first months of the year, more than twice as much water fell as usual (between January and April an average of 477.2 litres per square metre). Y after several downpours that cooled the ground and brought up streams that had been dry for too long, the warmest June on record.

In the midst of this climate chaos, the Non plus ultra project has continued to strengthen the communities of southern Badajoz, searching for narratives (mythologies we could say) with which to resituate ourselves in the consequences of the colonial extractivism that is at the root of the climate crisis. We reconvened "Water springs forth without warning" so that last year's event would not be a one-off, one-off event, but an annual celebration organised by the local community.with some elements that are repeated and others that vary, but above all fed by the desire of a group of people to get together at a significant moment (the solstice, the end of school, the beginning of summer... it doesn't really matter which one). This may be how traditions begin: with gatherings that are repeated because they help to give meaning to the world we inhabit.

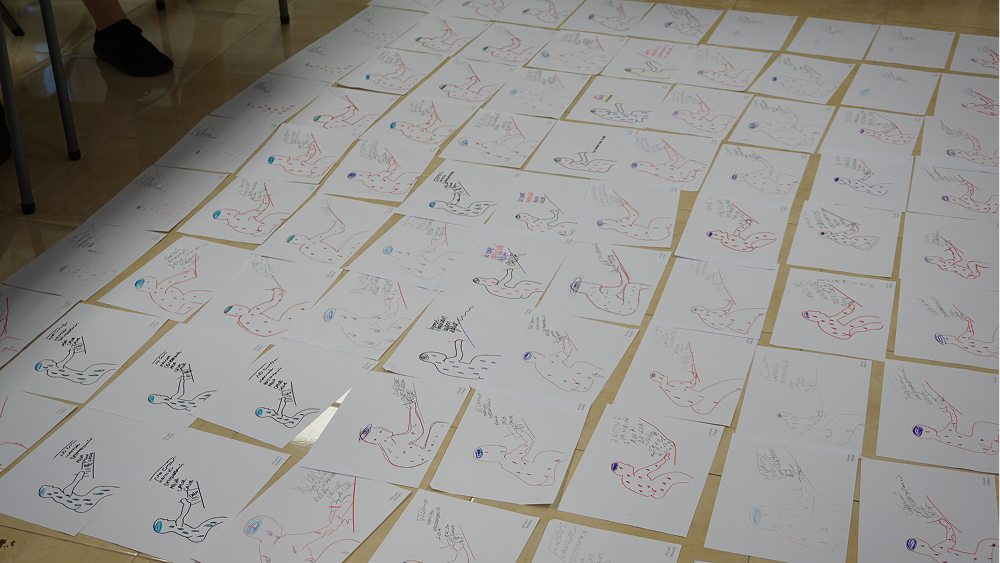

This year, "El agua brota sin avisar" coincided with the completion of the intervention with which the artist Francesc Ruiz is responding to the commission from Non plus ultra (to be presented publicly next October). His proposal focuses on the spaces of circulation of histories and communities in the transformations of the landscape of "diffuse urbanities", observing the secret flows of the territory. Based on this research, we decided to hold a fanzine printing and desktop publishing workshop, to share resources and collective strategies to tell stories connected to the territory. The workshop quickly turned into a NO PRINTING workshop NO FANZINE NO COMIC NO SELF-PUBBISHINGThe accident was triggered by a small accident: the risograph machine we were going to work with stopped working.

This incident (logical in a machine that is more than 20 years old, that has undergone many journeys and has given as many joys as moments of frustration) triggered a reflection on the logics of the self-publishing circuits in which as much ink as sweat is spent, and the need to generate generous modes of distribution, thought from the care and resources we have without entering into dynamics of self-exploitation. Reflections that gave shape to a system of reproduction that "printing" without a printer, generating collective images and a chain of copies open to interpretation and variations. Turning drought imaginaries and their limitations upside down, in a couple of hours a publishing project, "Ediciones potables", and an edition of 86 copies emerged to distribute in the village.

The workshop ended near sunset, as the heat was beginning to recede and the light invited us to go out and explore the post-industrial landscapes of the old cement works in Los Santos de Maimona. Among the ruins of the last century, a strange white figure, nicknamed "cigüedrag" by some participants, invited us to follow it. A magical gesture was repeated that at last year's event had led us out of the village and into a quarry. This time he led us through the concrete debris to an olive grove while we connected hoses and tried to keep them from getting tangled in the thistles and stones. We were instructed to carry water, but we didn't yet know what for.

The last section of the hose was a tube with perforations for watering. On arriving at the olive grove, Élan d'Orphium began to knot it with the irrigation pipes that were already installed in the olive trees. The process was complicated and could only be done collectively, holding here, lifting there. Several arms were getting wet as the water moved through the air.

Olive trees have always been a rainfed crop, adapted to harsh climates and dry seasons, but in the last decade they have been intensified with irrigation systems. With the drip infrastructure they produce more olives faster, but they have to spend a lot of water on land where it is not plentiful. Tall olive trees with gnarled trunks and centuries-old trees are being replaced by very small espalier-planted olive trees, more can be installed in the same space and it is desirable that they produce olives without growing tall to make harvesting easier.

The trees that we intervened next to Élan d'Orphium were not intensive shrubs, but they had the irrigation system, in a border zone between traditional cultivation and a small industrial push. With satin ribbons, he slowly led the water coming out of the pipes to small earthy objects on the ground. We waited, listening to the pattering of the drops, slowly, as the sun went down. A group of people in the middle of an olive grove observing the irrigation system intervened for something else, something small and mysterious, until Élan d'Orphium considered that enough water had fallen through the coloured ribbons and offered the object to one of the assistants: it was a clay whistle which, when filled with water and blown, produced the trill of a bird.

The action was repeated several times, other coloured ribbons and mud birds drinking. And each time one was filled, a new chirp appeared. Before long, the whole group was blowing and twittering, the olive grove went from the silence of dusk to a feast of birds scattered in the shadows of the field. Élan d'Orphium had "hacked" the irrigation system to escape the productivist logic that threatens aquifers and a speculative approach to common resources. The implementation of irrigation systems, which many farmers are forced to implement in order to survive in an increasingly competitive speculative market, not only means increased water use on land undergoing desertification, but also sometimes leads to indebtedness in order to invest in installations and accelerate productivity. Soil and water become cogs in a financial machine. Faced with this short-term use of water, the concert of clay birds (pieces from Salvatierra de los Barros, with a long pottery tradition) was a provocation to think about how important it is to irrigate as well as to chirp, that the tinkling of the drops should be appreciated for what it is and for what it can unexpectedly provoke, beyond its possible economic profitability. It is not only important that there is water, that there is rain, but how we relate to it, if we are able to understand it as part of a living ecosystem and not as an investment good.

We returned to the abandoned cement factory at last light. The UHT collective has its work space there and had prepared a "sound aquifer" to dance with DJs Bizantina and Ramaseca. We celebrate with the clarity of knowing that the aquifers under our feet continue to dwindle and the air we breathe continues to be polluted by cement production, but we also celebrate with the clarity of knowing that we are not alone. with an eye to other horizons, other imaginaries that transform industrial ruins into prefaces to new stories, giving another meaning to the world we inhabit. This is how traditions emerge.

Concomitentes

Concomitentes