“The claim for a plural and public space becomes a dream of other future spaces”.”

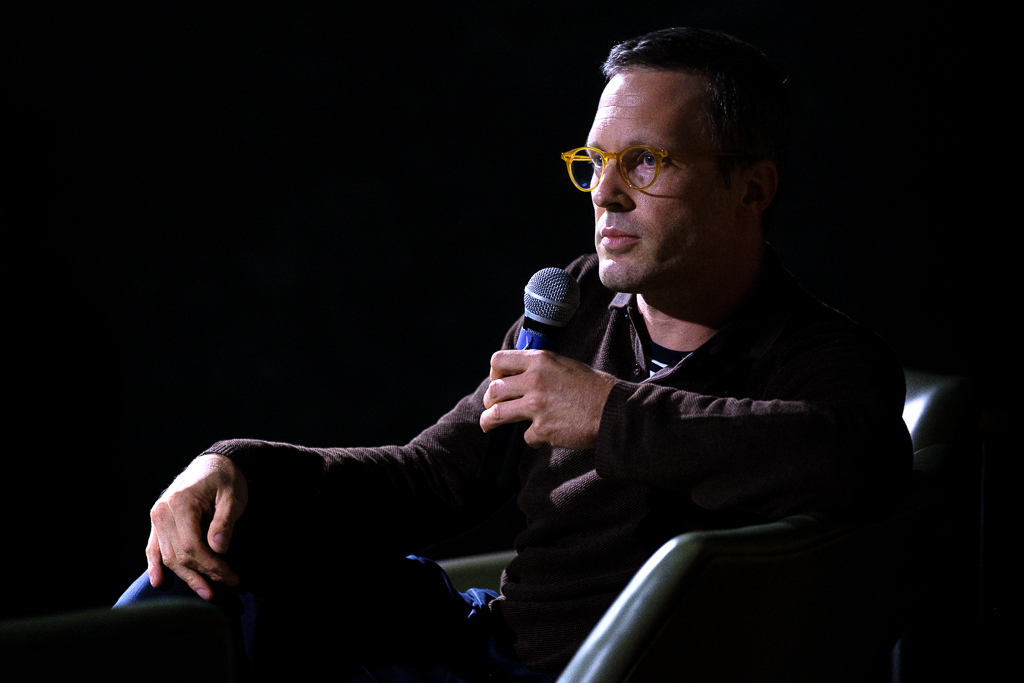

Conversation between the co-editors of 'Mutaciones en el espacio público'. Fran Quiroga and Sören Meschede; and the mediator of the concomitance UCI Pediátrica, Felipe G. Gil from ZEMOS98.

With the launch of his first book, Mutations in public space, Concomitentes aims to deepen reflection, research and open debates on the themes that are at the heart of its practice. In this conversation, Felipe G. Gil, from ZEMOS98, mediator of the concomitance Paediatric ICU, talks to Sören Meschede and Fran Quiroga, who edited the publication, about the relevance of this book.

FELIPE G. GIL: Why do we want to make this book?

SÖREN MESCHEDE: Perhaps it is important to say that we have always thought of generating a certain publishing activity. On the one hand, we want to make books to document the processes of concomitance, seeing that these are long, invisible and very little tangible. On the other hand, we take the example of the New Commanders of France and its collaboration with the publishing house Les presses du réel, with which there are not only books documenting the concomitances but also a series of more theoretical publications, not linked to a specific project, making New Commanders to establish itself as an important agent within wider cultural and social practices. We have transferred the same idea to Concomitentes.

FRAN QUIROGA: The conception of art as research, how it expands the ways of investigating reality, Concomitentes' own projects work from this conception. How to make this editorial commitment reflect this way of approaching reality, which will help in its replicability, which I believe is one of the key elements when thinking about the pertinence of generating a theoretical production in book format.

«This particular publication responds to a need to contribute to such an unusual problem as that of a pandemic and to contribute through art, with the modesty of not giving answers, but rather providing a space for debate».»

If we consider that art is interdependent, that it is connected with reality, giving answers to life, something had to be done. From there arose that desire and that search for complicity with other people who would help us to understand the complexity that this crazy time has brought with it.

FGG: Knowing that public space is a place for negotiation and a place that art has traditionally claimed to represent under-represented communities or issues that reflect on the status quo, in a post-pandemic context where there are restrictions on the use of common space, how does the book work this paradox?

CF: One of the issues pointed out in the book is how citizens manage themselves and how we should be grateful for this collective effort. I think there is also a questioning of this idea of control that is increasingly being assumed, it is important to underline that it was the citizens who, faced with this situation, decided that we could not use this public space and be so close to each other. There was a process of co-responsibility and collective care, something we had never done before, because we had never been confronted with something like this. Other mediation mechanisms were also activated, other ways of being together in that distance, which allowed us to deal with that physical separation in another way, in a kinder way, experiencing other ways of being together in the distance, many of them being able to remain in time.

SM: Many of the voices in the book vindicate this heterogeneous and informal space in dispute, longing for the possible loss of this. But the texts do not stop there, as Fran says, they go further. What runs through several of them is the vindication of the capacity of cultural practices - expanded, including here urbanism and architecture - to help, to project and to dream.

The crisis, which came before covid, has made us very cautious when it comes to dreaming, art and culture can help us to project ourselves into the future, they can be a real driving force for change so that things really happen. The vindication of a plural and public space becomes a dream of other future spaces.

FGG: A somewhat misleading judgement is often applied to collaborative artistic practices, a very common one, about their inaccessibility with regard to the use of language and their tendency towards elitism. We also know, those of us on the inside, that where others see an abstract and inaccessible language, what is really going on is an experiment and the creation of a social imaginary where it is necessary to try everything, including new ways of naming. How does the book dialogue with this?

SM: Absolutely right. The issue of communication in these participatory projects is fundamental. Everything we are doing has an afterlife of its own work, it seeks a vindication and visibility of certain problems.

Making this reflection visible requires a certain abstraction, naming certain concepts that are difficult to understand, which can generate problems of understanding. In this sense, we must be clear that the book is not a tool for mass dissemination, but a formula for initiating a discourse among professional-cultural agents who are interested in this reflection.

Therefore, the book is certainly one way of communicating, but it should never be the only way. We must open up to other formulas that go further and explore other ways of interconnecting with different sectors of the public. This series of books that we are proposing is very much aimed at a certain type of non-academic, but professional, public that is theoretically interested in the issues we are dealing with. From there we must translate it to other places, for example, a podcast would be a way of translating this type of content for other sectors and audiences.

CF: There is a willingness to generate a discourse in an accessible format. We also have to be honest, to know who we are addressing. We must be aware of this verbiage, of the fact that there is hyperbole that does not help understanding. This desire to make ourselves more accessible cannot result in a loss of discursive power, but the real challenge is to know how to tell something profound in the simplest possible way. Sometimes this is achieved, sometimes not, but this will must exist in order to transcend those recursive communities of agents that operate in the art world.

FGG: That dichotomy is a tricky one, for example, for a long time the word ‘heteropatriarchy’ was mostly part of academic and feminist activist production, today it has filtered down to a point where many people know what we mean, they don't see it as alien. It is a constant challenge to be accused of being elitist, when we are trying to collect this experimental discursive production, at the same time as we want to get out of the cultural ghetto and reach other places. With regard to the configuration of the books and taking as a metaphor the pairing that combines wine with what you are going to eat, what common themes would you say that combine or link all the texts?

CF: The book is divided into four large blocks, each with three texts. We deal with the normativisation of public space, the importance of the minor and the idea of the everyday, in those small actions that are constructing the hyper-productivist imaginary. We also deal with the idea of public time, how speed and rhythms have been reconfigured. At the same time, allusion is made to how the museum was already the antechamber of pandemic distancing, and we ask ourselves how to rethink art as a facilitator of a place of encounter? This book not only poses a critique, but also opens up alternatives for debate.

SM: To continue with the culinary imaginary, Felipe, the proposal of blocks, as a starter, first, second course and dessert, would not have to be like this. The ice cream could come first, and then move on to the wine. There are themes that are present in some way in all the texts, such as, for example, the allusion to the future and the capacity for dreaming. Other themes are that of ecologies or relationships of mutual care and the frictions generated by the pandemic. Thus, the words ‘crisis’ or ‘pandemic’ are mentioned in almost all the texts, but we have insisted that the book should not remain a mere account of pandemic issues, with an expiry date, but go beyond this immediate experience. In this sense, some of the texts are pre-pandemic, rescued from other publications, which speak of other crises or moments, so we claim that what has happened is exceptional, but also responds to a certain pattern of crises that we have already lived through. We must always appeal to this capacity to overcome.

FGG: What future life do you imagine for the book?

SM: This is the first of a series of books, so this first publication sets a precedent for an editorial collection that we want to bring out with Bartlebooth, generating a channel that brings together different actors who think about public space and its relationship with art, citizenship and urbanism. On the other hand, we hope that these texts can be worked on in other more informative formats, in meetings and workshops that we want to hold later in the public presentations of the book.

CFWriting is an act of reparation, which allowed us to get out of this monotonous life brought to us by the pandemic life, by doing this exercise of small abstraction when we started to write. It would be nice if this were reciprocated, if reading the book were also an exercise of reparation, -social and collective-, contributing to this thought from this exceptional moment. And, for me, there is another theme that runs through the whole work, and that is what imaginaries the pandemic leaves behind, what legacies that look at the other leaves behind, beyond the deaths and the pain. The book can be read from that joy of continuing to work together, and that has to prevail. The pandemic was just another crisis, and we must trust in society's capacity to adapt, although I do think it would be serious if this fear of being with the other persisted, and the book should help to reverse that.

Concomitentes

Concomitentes